UT Alum Left Lasting Impact on Chemical Extraction

Chemistry is frequently called the central science. Because it uncovers knowledge critical to the understanding of matter, it is important to a number of disciplines. Discoveries and innovation in chemistry can have far-reaching implications that last for decades. The great-grandson of alumnus Edgar Stanley Freed came face to face with this phenomenon when he began researching his family’s history.

E. Stanley Freed came to the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, in 1909. He joined the Department of Chemistry, earning a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering in 1913. Freed then served two years as an assistant professor at UT, until beginning graduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Freed received one of only four PhD degrees MIT awarded in 1918. In 1920, he began working in the New York laboratory of the Chile Exploration Company, and in 1922 he relocated to Chile.

Building a Legacy

By the time Freed arrived in Chile, the nitrate industry had been suffering for a number of years, due to the development of synthetic nitrate. The Chile Exploration Company sent Freed to an experimental plant for nitrate extraction working with caliche, a type of soil containing a variety of mineral deposits including nitrate salts. He was tasked with modernizing the industry by developing better, more efficient processes.

Upon his arrival, Freed realized little research had been done on the caliche itself and its chemical properties. He quickly began developing a body of knowledge that could be used to inform extraction methods. Over the course of his career, Freed and a number of additional researchers made advancements in mineral extraction from caliche.

By the mid-1940s, Freed had begun to pursue not only nitrates, but possibly useful byproducts. He would eventually be credited with developing the solar evaporation pond, a method that uses the natural process of evaporation in a series of open-air ponds to extract a variety of products.

Freed’s evaporation ponds became an industry staple and are still used today. This method has been used to efficiently recover nitrates, iodine, potassium, and even lithium. It is still considered a key element of production in industry, and contributes to a range of fields including pharmaceuticals, construction, and agriculture. Lithium alone has been used to power personal electronics, medical devices such as pacemakers, and electric vehicles. Freed’s development helped prop up a declining industry and simplified access to materials that have been used to create a number of elements of modern life.

Preserving History

Sebastian Freed-Huici began investigating his great-grandfather’s history in earnest at the age of 14. Freed-Huici had been taught that the nitrate industry in Chile collapsed due to a combination of the Great Depression and the creation of synthetic nitrate. However, he knew that Freed had been working in the industry up until his death in 1950. Unable to reconcile these differing timelines, Freed-Huici began digging into his family’s records, uncovering more of Freed’s story.

“My grandmother kept a folder about my great-grandfather with some newspaper clippings and other information about him,” said Freed-Huici. “She also had his diplomas from the University of Tennessee and MIT. After that, I looked for information about him online and then started calling historians.”

Freed-Huici eventually connected with a historian at the Archivo Nacional de Chile who had recently uncovered boxes of documents about and belonging to the late E. Stanley Freed. It was in communicating with the historian, Pablo Muñoz, that Freed-Huici learned of his great-grandfather’s achievements.

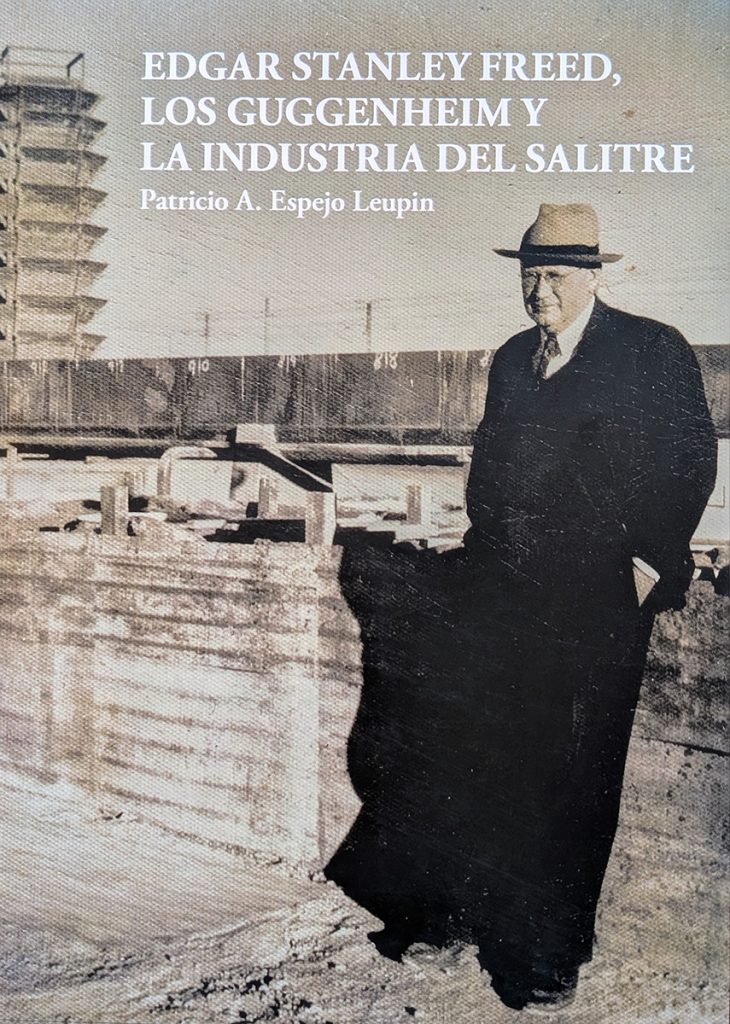

Galvanized by this discovery, Freed-Huici set out to share Freed’s story and, in the last few years, all that effort has begun to see results. In 2021, a book detailing Freed’s life and work was published. Edgar Stanley Freed, Los Guggenheim y la Industria del Salitre was written by Patricio A. Espejo Leupin and included images and documents provided by Freed-Huici. A second book, written by industry professional Beatriz Oelckers and titled El Hombre Que Más Sabía del Caliche en el Mundo, was published in August 2024.

Freed-Huici, now a PhD student in economics at the University of Chicago, said he was inspired by his great-grandfather and wanted to share his story.

“I realized that this is not a story of the past. It’s a story of the present, because all these systems are used today,” said Freed-Huici. “His legacy is alive, and I want people to know about it. For the 28 years he was in Chile, he never stopped working on this problem. He never stopped researching and experimenting and looking for answers, and I find that very inspiring.”