Sheng Dai Among World’s Most Highly Cited Researchers for 10 Years

Sheng Dai, professor of chemistry, is one of six faculty members from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville to be named to Clarivate’s Highly Cited Researchers list for 2025, an honor bestowed on only one in 1,000 of the world’s scientists and social scientists. The designation recognizes researchers whose publications are among the top 1% by citations in their respective fields over the past decade.

“Being named among the world’s most highly cited researchers is a powerful testament to the global impact of our faculty and students’ work,” said Deb Crawford, UT’s vice chancellor for research, innovation, and economic development. “We are incredibly proud of these scholars, whose research continues to shape their disciplines and strengthen UT’s reputation as a leader in research that impacts the world.”

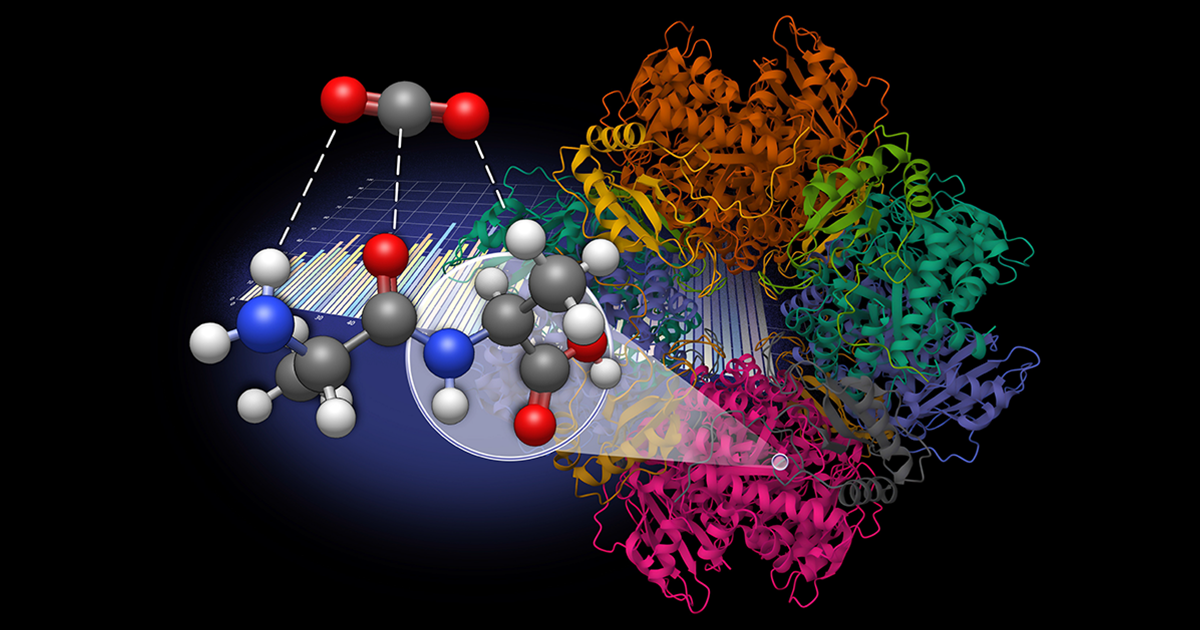

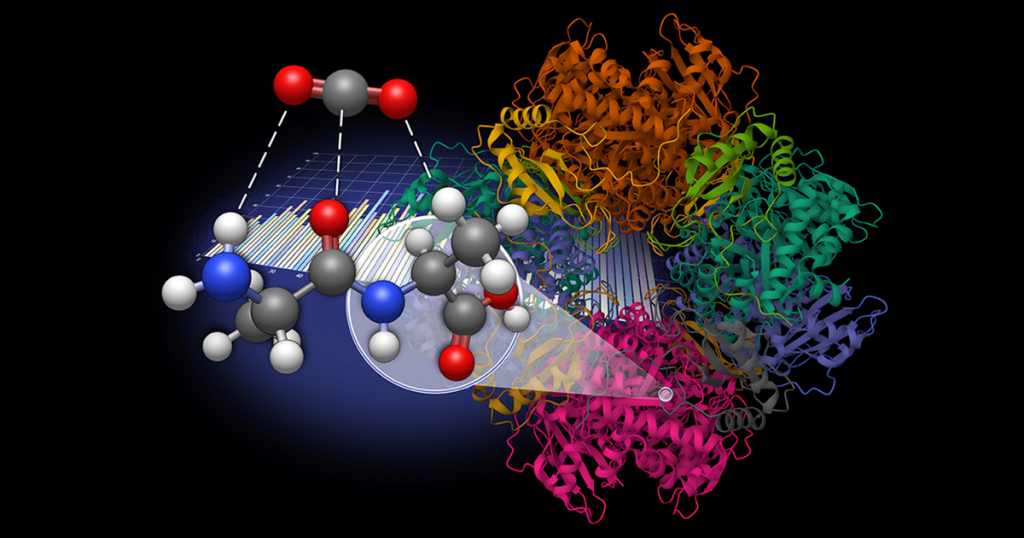

Dai, who holds a joint faculty appointment at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, has been named to the Highly Cited Researchers list for the 10th time. His work focuses on developing advanced materials for energy-related applications, particularly in areas like ionic liquids and molten salts, advanced separation processes, high-entropy materials, electrochemical processes and sustainable carbon transformations.

Dai is currently studying ionic liquids and porous materials to learn how they can be used for separating different substances, storing energy and speeding up chemical reactions. He is also developing ways to turn plant-based carbon into graphite, which can be used for storing energy.